The Middle Class is Dying. Can it be Saved?

For America's middle class, hope for the American dream is at an all-time low. The all-important middle class is disappearing - and many of those of those families fall into the lower income class.

For many generations, we Americans have touted the middle class as being s litmus test for how America is doing. Traditionally, when the middle class has thrived, the country has thrived. And when the middle class has suffered, so has our nation. And there is widespread agreement among Americans that the middle class is supremely important to the economic future of the US, not to mention its role in the nation's ability to remain competitive in the global market.

According to a 2019 report by the OECD [1], "a strong and prosperous middle class is crucial for any successful economy and cohesive society. The middle class sustains consumption, it drives much of the investment in education, health and housing and it plays a key role in supporting social protection systems through its tax contributions." Middle-income households contribute more than any other income group to aggregate consumption in the economy [14].

Yet despite broad understanding and acceptance of the importance of this demographic group, the US middle class has continued to falter over the past 40 years -- both in terms of sheer size and economic performance. The share of aggregate U.S. household income earned by middle class families has fallen steadily since 1970, when adults in middle-income households accounted for 62% of the U.S.'s total aggregate income. By 2020, that share had fallen to 42%. During the same period, the share of aggregate income accounted for by upper-income households dramatically increased from 29% in 1970 to 50% in 2020 [4].

I live in Florida, so I'm going to use the Floridian definition of the middle class "bucket" in the histogram of society. But the definitions below applies fairly uniformly (with some wrinkles) across the United States [2].

Defining the “Florida Middle Class”:

- Middle household-income range $54,828 – $87,656

- Median household income: $63,062 (15th lowest in the US)

- Share of income earned by middle class (middle 20%): 14.1% (4th lowest in the US)

The share of income earned by wealthiest 5% of households in Florida is 24.4% (3rd highest), demonstrating the income gap between the middle class and the upper-class.

In Florida, we -- like California, New York and a few other States, also have a cost of living factor that needs to be added in to this analysis: Floridians have a cost of living that is 0.7% more than the U.S. average (15th highest in the US).

Statistically, there is little doubt, economic or otherwise, that the middle class is rapidly shrinking [3]. In 1971, the middle class represented about 71% of the American population. This shrank to 50% by 2021. In the meantime, the size of both the upper and the lower class increased substantially (population count), over the same period.

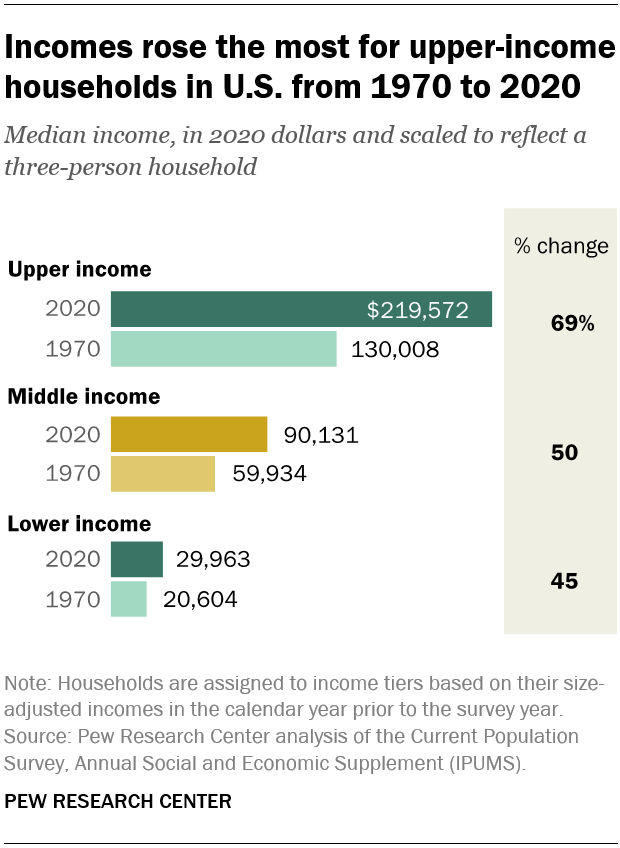

But this is not only a population counting game. If one takes a look at the growth in income of the three classes, there is a large red herring that appears [4]. The rise in income from 1970 to 2020 was steepest for upper-income households. Their median income increased 69% during that time span, from $130,008 to $219,572. In comparison, over the same period, the income of the lower class increased by only 45%.

To use an old aphorism, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer. The data presented above regarding the plight of the middle class over the past four decades is inexplicable in the sense that our economy has generally expanded during that period. One has to wonder whether the factors influencing the disappearance of the middle class is really little more than a lightly-veiled realization of class warfare. The size, wealth and power of the elite class has substantially increased and a significant fraction of the former middle class has slipped below the line in the "lower class" category -- and all of this during a period of post-war prosperity.

There are multiple reasons influencing this, of course. I'll discuss a few of the important ones below.

Retirement Savings and Social Security

“The middle class is left behind by the retirement savings system in key ways,” report authors Tyler Bond, the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) research manager, and Dan Doonan, the executive director [5].

The Social Security replacement rate is the ratio of gross income received in retirement divided by pre-retirement gross income. Doonan states that “Social Security replacement rates are too low for middle-class families to maintain their standard of living in retirement, but many middle-class households don’t reach the level of income and savings needed to truly benefit from the tax incentives for individual savings.

Congress has established a number of tax incentives to encourage saving for retirement through employer-provided defined benefit pension plan or 401(k) plan, or on their own through an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) plans. However, due to the structure of the tax code, uneven levels of retirement plan participation, and the growth of income inequality, many of the benefits of these tax incentives accrue to high-income earners. The middle class too often is missing out on the benefit from various retirement savings programs.”

In short, we have a progressive Social Security system specifically designed to help the lowest earners -- and a tax break system designed to help the highest earners. But guess which group is missing out?

While Social Security benefits tend to be generous to people at very low income levels, Social Security replacement rates drop off quickly for those in the middle class. The problem is that existing tax incentives do not fill the gap until a taxpayer reaches significantly higher income levels.

In the case of Social Security, the percentage of earnings above the taxable maximum amount for earnings and benefits ("tax max") has increased due to the increased amount of income inequality in the U.S. But this income shift is not subject to Social Security contributions, because of the tax max. Eliminating the taxable maximum amount for earnings and benefits completely would bring more revenue into the program and ensure the solvency of Social Security.

Taxes

People making $500,000 a year, are paying a 37% marginal federal taxes, plus state, city taxes. But the real problem is those who are making $500 million a year, or more, whose marginal tax rate is effectively 0%. A billionaire making their money through wealth — such as direct stock ownership, or by running a private equity or hedge funds — needs to pay little if any tax [6]. They can borrow against their untaxed fortune, tax-free. Or they can use the “carried interest” loophole on their funds.

Beginning in the late 1970s, something fundamental began to shift in the American economy. During the thirty year post-war period, gains from economic growth were broadly shared between the classes, which resulted in higher incomes for both those at the bottom and the top.

By 1975, economic gains went mostly to the top income classes. And, as a result of this, there has been a noticeable rise in inequality in terms of both income and wealth in the American economy. For a white male without a college degree, real income is lower now than it was in 1975. Median income, (full-time, full-year) workers experienced little real wage growth during the past forty years. However, those at the very top have seen wage growth that significantly exceeds GDP growth [5].

In 1981, the Reagan administration directed the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to change the legal interpretation of a provision of the tax code [6]. The change essentially made the 401(k) programs created by the Revenue Act of 1978 more widely available. But the underlying impact of this change was to not only shift the responsibility and risks of retirement onto individuals, but also a significant portion (if not all) of the costs which had previously been borne by employers. The middle class, which constitutes slightly more than half of American households, has borne the brunt of this cost shift [5].

As we look into the future, there are many people who are approaching retirement with a Social Security benefit that will replace less than half of their pre-retirement income. Most of these families have meager savings, and are much less likely to be accruing a pension benefit than the middle-class workers of past generations.

Because interest rates have been at historically low levels in recent years, investors must either take more risk or plan for lower returns in their investments by saving more.

Considered together, these changes result in a situation in which a typical middle-class family receives a smaller tax benefit through saving for retirement in a plan like a 401(k) than a similar family forty years ago. But the reality is that they are approaching retirement with a highly impactful need for more financial resources for a secure retirement.

Inflation

And now inflation is adding icing on the cake that is destroying the middle class [9]. For this income group, prices are increasing faster than their income, according to a September report by the Congressional Budget Office. The share of adjusted market income that would be required to purchase a "consumption bundle" declined for households in the lowest and highest income quintiles. However, it increased for the middle-income quintiles. Households in the lowest and highest income groups saw their income grow faster than prices over the same time period, the report found.

As a result of all this, middle-class Americans are dipping into their savings accounts and running up credit card balances. That leaves them more financially vulnerable in the event of an economic shock. Some have described this as the “running to stand still” phenomenon.

Major Life Cost Increases

The expenses that middle class families typically encounter still include major life costs–such as college, health care, and child care. The costs for these major budget expense items continue to rise at a rate that outpaces the rate of increases in income. As a result, consistent savings opportunities in the middle class demographic often seem out of reach.

In 1980, the price to attend a four-year college full-time was $10,231 annually—including tuition, fees, room and board, and adjusted for inflation—according to the National Center for Education Statistics. By 2019-20, the total price increased to $28,775. That’s a 180% increase [11] Per capita health expenditures grew 549 percent (adjusted for inflation) between 1963 and 2012 [12].

In the last two decades, house prices, in particular, have outpaced CPI inflation and household median income. Almost one-third of the budget of the average middle-income household goes to housing, on average [14].

The rate of growth in health care spending in the U.S. has outpaced the growth rate in the gross domestic product (GDP), inflation, and population for many years [13].

During the 60’s most women with young children did not work outside the home. But starting in 1968 and continuing through 1995, the labor force participation rate of married mothers grew from 27 to 65 percent. Labor force participation among single mothers grew from 45 percent in 1968 to 77 percent by 1998. Unfortunately, the U.S. government first began collecting information about the cost of child care in the early 1980’s. The issue here is less the cost of child care, than it is the number of people who now require access to it. If normalized for inflation, the cost of child care from birth through the age of 17 in 1968 was $198,560 (in 2013 dollars). In 2013, the cost of child care from age 0-17 was $245,340 (an increase of 24%, after inflation). But because the much, much larger number of mothers participating in the labor force, high child care costs became the routine, rather than the exception for middle class families [15].

What it all means

For America's middle class, hope for the American dream is at an all-time low, according to the latest Gallup poll, which tracks Americans’ assessments of the next generation’s likelihood of surpassing their parents’ living standards.

Gallop reported that 59% of middle-income Americans (those making between $40,000 and $100,000, according to Gallup) believe that it is very or somewhat unlikely that today’s young adults will have a better life than their parents. In the lower income classes, only 48% of those with annual household incomes under $40,000 feel that way [10]. This is very telling in terms of the outlook for the middle class.

The U.S. retirement savings system is structured to leave out the middle class. Social Security, while very effective at reducing elder poverty, is structured with replacement rates that diminish rapidly as income increases, even at middle-class income levels.

While the individual savings system offers generous tax incentives, it provides the greatest benefit to high-income earners and middle-class workers often are not

well-positioned to take advantage of it.

The tax code it set up to offer much of the benefit to the top income classes, since high-income taxpayers benefit more from deductions in the current income tax structure.

With rising inflation middle-class America is dipping into its savings and running up credit card balances — leaving them more financially vulnerable in the event of an economic shock and less able to make ends meet on a week-to-week basis.

As a result of all these factors, the middle class is disappearing - with many of the former middle-class falling into the lower income class category, rather than moving up.

Sources:

[1] https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/OECD-middle-class-2019-main-findings.pdf

[3] https://www.barrons.com/visual-stories/who-is-middle-class-01652277488

[5] https://www.nirsonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/NIRS-The-Missing-Middle-1.pdf

[7] https://www.guideline.com/blog/evolution-of-401k/

[8] https://www.epi.org/publication/the-state-of-american-retirement-savings/

[9] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-09/58426-Inflation.pdf

[10] https://news.gallup.com/poll/403760/americans-less-optimistic-next-generation-future.aspx

[11] https://www.forbes.com/advisor/student-loans/college-tuition-inflation/

[12] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1024

[13] https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/effect-health-care-cost-growth-us-economy-0

[14] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/e2352f43-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/e2352f43-en

[15] https://winstonprouty.org/cost-of-child-care-50-years-ago/